In the sun-soaked hills of Pacific Palisades, California, Case Study House #8—better known as the Eames House—stands as a quiet icon of modern American domesticity. Designed by Charles and Ray Eames between 1945 and 1949, this architectural gem is as much a home as it is a manifesto in steel, glass, and colour.

The Eames House does not rely on grandiosity or ornament. Instead, it tells its story through its materials: modest, industrial, playful, and deeply purposeful. From its modular steel frame to its kaleidoscopic panel façade, every choice reflects an ideology that fused postwar optimism, industrial innovation, and aesthetic restraint. This blog explores how the Eames House's material palette embodies its design philosophy and reveals how thoughtful sourcing of building materials can transform structure into narrative.

A House Framed in Steel and Optimism

At the heart of the Eames House is a lightweight, prefabricated, and economically efficient steel skeleton. Using 4-inch H-columns and 12-inch deep open-web steel joists, the architects collaborated with engineer Edgardo Contini to create a modular structure that minimized material waste while maximizing spatial flexibility.

This approach was both a technological and ideological choice. Following WWII, the U.S. sought to redirect wartime industrial advances—such as aircraft production—toward peacetime prosperity. The Eameses embraced this ethos, using materials once destined for military hardware to build a domestic haven.

Steel, in this context, was not cold or corporate, but rather allowed for a fast, inexpensive, and replicable building process that echoed the spirit of the Case Study House Program: to address America’s postwar housing crisis with industrialized solutions that remained architecturally humane.

Transparency and Privacy in Glass

Perhaps the most arresting feature of the Eames House is its alternating rhythm of opaque and transparent façade panels. Floor-to-ceiling glazing—sometimes divided into smaller panes—creates dematerializing reflections from the outside and frames curated views of eucalyptus trees and ocean vistas from within.

This juxtaposition enacts the Eameses' philosophy of “life as performance,” where transparency invites nature, light, and openness into the daily routine of the home. Meanwhile, the more private portions of the house use colored or neutral panels for privacy, especially in the bedroom and work zones.

In terms of function, glass here is both spatial and psychological. It erases hard divisions between inside and outside. It also activates what the Eameses described as “the whole vast order of nature” as part of the domestic experience.

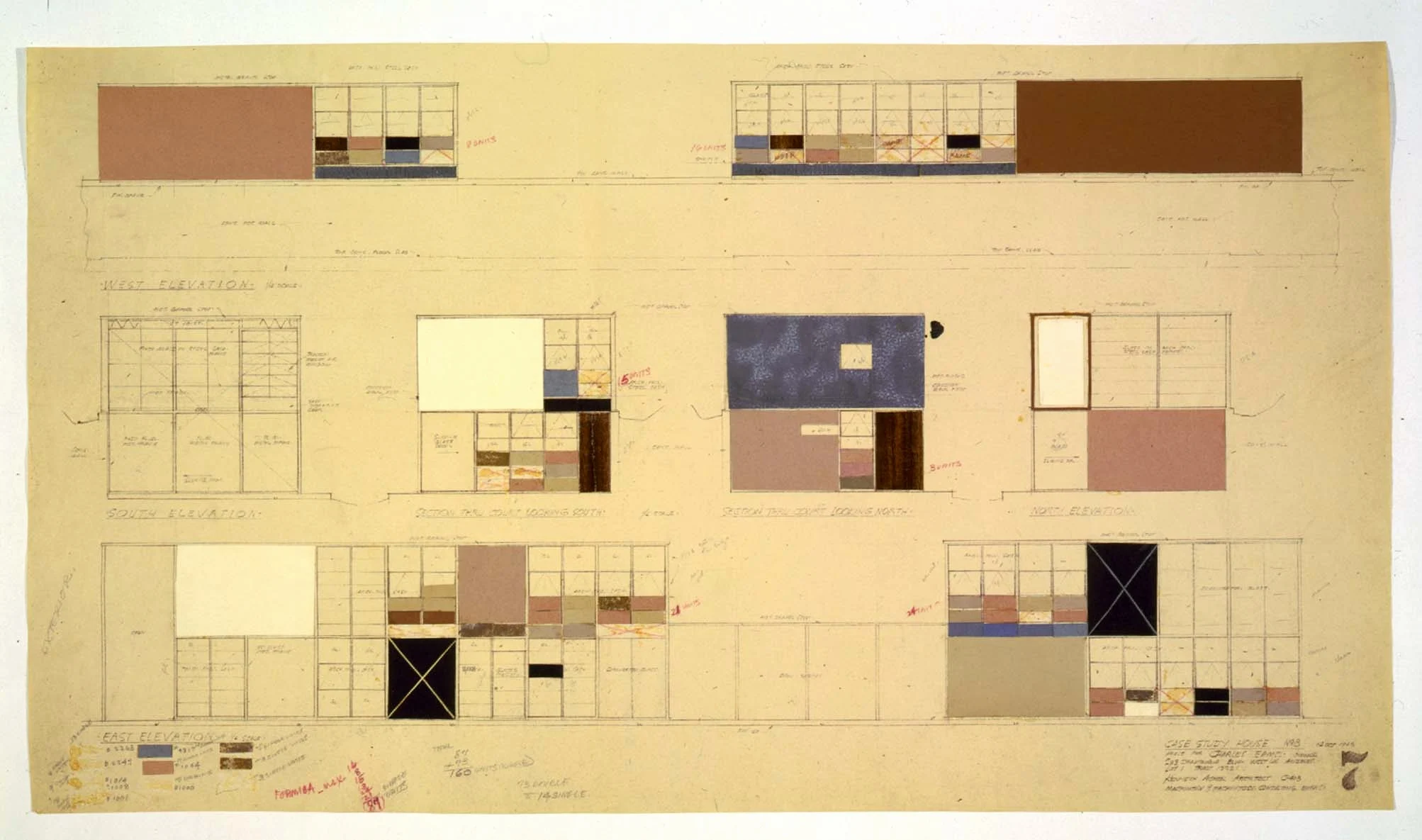

Painted Panels as Emotional and Spatial Modulators

Ray Eames, whose background in fine art shaped much of the house’s sensory language, introduced color as a vital material. Solid panels painted in primary hues—red, blue, yellow—and more muted shades like black and cream, punctuate the otherwise austere frame.

These painted Masonite or fiberglass panels serve both symbolic and spatial functions. Visually, they evoke European modernism and the De Stijl movement, which Ray Eames had direct contact through her exposure to Piet Mondrian. Functionally, the colors create zones of activity and rest, celebration and concentration.

Importantly, while they reference global movements, the color panels also root the house in a local American vernacular: the playfulness of 1950s optimism, the brightness of California light, and the visual rhythms of mass production.

Concrete, Brick, and Timber: Grounding the Frame

Though the Eames House floats visually, it is materially grounded in concrete and brick. The foundation is a concrete slab, and the patio flooring uses brick pavers, lending texture and tactile warmth to the otherwise industrial palette.

Inside, the back wall of the living room is timber-paneled, offering a soft counterpoint to the steel structure and echoing the Eameses’ broader fascination with folk materials and natural finishes.

These materials remind us that innovation doesn’t necessarily demand newness, but rather thrives in juxtaposition. Concrete’s weight grounds the house, while timber warms it, and steel elevates it. Together, they form a balanced material narrative.

Prefabrication as Poetic Assembly

Beyond each material’s inherent character, the way each material comes together is what defines the Eames House. The modular frame, the infill panels, and the floor tiles and cabinetry were designed for prefabrication. Materials were sourced from catalogues and repurposed creatively, embodying a spirit of design improvisation within constraint.

The façade’s layout was modified on-site when the pre-ordered components arrived in an incorrect configuration. Rather than scrap the materials, the Eameses rethought the design, creating a structure even more spatially and aesthetically compelling than the original blueprint.

A Studio and a Sanctuary

The Eames House comprises two volumes: the residence and the adjacent studio, separated by a landscaped courtyard. Though united in material language, the two serve different functions: living and making.

Materials reflect these roles. The studio space features a simpler palette with parquet floors, painted steel, and modular shelving to support the Eameses’ prolific work in film, design, and exhibition. The home space, while using the same frame, is layered with textiles, books, folk art, and personal objects.

Together, they form a total environment, with materials enabling a seamless flow between creativity and comfort.

Contextualizing the House Within Its Landscape

While the Eames House is often celebrated for its interior warmth and industrial elegance, its relationship to the landscape is equally critical. Built against a sloped embankment and partially screened by eucalyptus trees, the structure nestles rather than dominates.

Unlike modernist homes that often impose upon nature, the Eames House accepts the site's existing contours. Its materials echo this humility: the matte steel and reflective glass absorb changing light; the colorful panels harmonize with seasonal shifts.

Materiality as Message: The House as Media

It’s no accident that the Eames House has appeared in fashion shoots, films, and advertising campaigns. From the outset, Charles and Ray Eames were masterful in presenting their home as an icon through their own documentation, making it a symbol of postwar American possibility.

Their 1955 film House: After Five Years of Living reveals this vision, presenting the house not through architectural diagrams, but through color-saturated stills of textures, objects, and light. In doing so, it elevates materials as the primary language of domestic life.

A Blueprint for Material-Sensitive Architecture

While the Eames House remains a singular expression, its lessons are far-reaching. It shows how architecture can:

Today, as architects and builders seek sustainable, expressive, and efficient materials, the Eames model continues to inspire. But realizing such vision requires not just good design—it demands access to trustworthy material vendors.

Contemporary practitioners can emulate the Eameses’ ethos through platforms like Venzer, which curates verified material vendors. Just as the Eameses selected materials that embodied flexibility and narrative potential, today’s architects must choose vendors who share a commitment to craft, transparency, and experimentation.

For Further Reading

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/992

https://www.eamesoffice.com/visit-learn/eames-house/

https://www.archdaily.com/66302/ad-classics-eames-house-charles-and-ray-eames

Works Cited

Blundell Jones, Peter, and Eamonn Canniffe. Modern Architecture Through Case Studies, 1945–1990. Architectural Press, 2007.

Eames, Charles, and Ray Eames. An Eames Anthology: Articles, Film Scripts, Interviews, Letters, Notes, and Speeches. Edited by Daniel Ostroff. Yale University Press, 2015.

Arts & Architecture. “Case Study Houses #8 and #9.” December 1945.

Stay in the loop with platform updates, success stories, and industry news.